Wang Ronghua

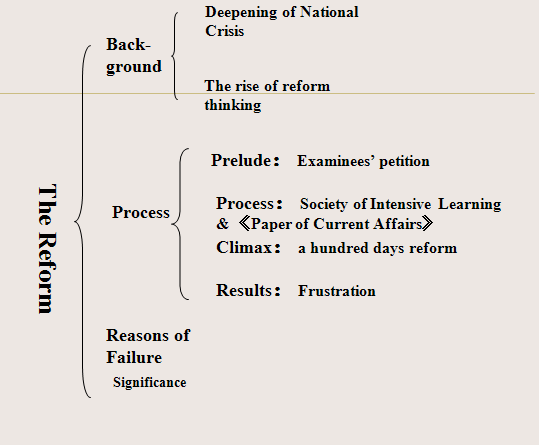

Hundred Day’s Reform

Key Points:

1、Background

2、Political views of the reformers, main contents of the Hundred Day’s Reform and analysis.

3、What lessons to be drawn.

A:Background

1、Economic Basis:The initial development of Chinese national capitalism

2、Class Basis:The growing of China’s national bourgeois class

3、Igniter Fuse: Sino-Japanese War of 1894; National Crisis

4、Ideological Basis:The Rise of Reform Ideas

As a result of defeat the Qing government was forced to sign the Treaty of Shimonoseki, ceding Taiwan to Japan.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki alone earned Japan 230

million taels of silver in extortion money,

about four and a half times its annual national revenue.

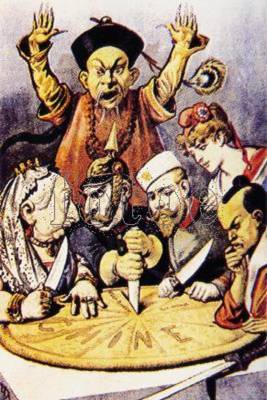

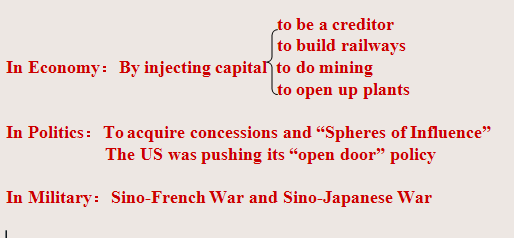

How Foreign Powers were Dividing China

In November 1897, Germany sent troops to Jiaozhou Bay of Shandong, Russians demanded the Northeast, France demanded Guangdong and Guangxi, the British asked for the Yangtze River regions, the US also demanded a piece of the pie after Japan took over Taiwan.

What Foreign Powers Did at the End of the 19th Century?

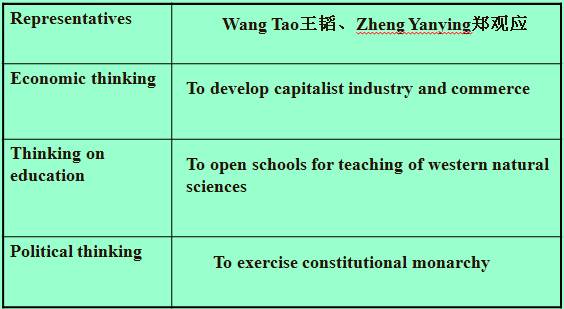

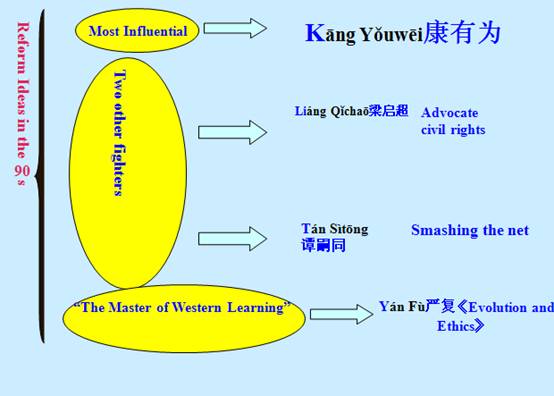

Reform Ideas in their Infantry

Kāng Yǒuwēi

Kang Youwei (simplified Chinese: 康有为; March 19, 1858–March 31, 1927), was a Chinese scholar, noted calligrapher and prominent political thinker and reformer of the late Qing Dynasty. He led movements to establish a constitutional monarchy and was an ardent Chinese nationalist. His ideas inspired a reformation movement that was supported by the Guangxu Emperor but loathed by Empress Dowager Cixi. Although he continued to advocate for constitutional monarchy after the foundation of the Republic of China, Kang's political ideology was never put into practical application.

Kang cited Confucius as an example of a reformer and not as a reactionary, as many of his contemporaries did. He argued that the rediscovered versions of the Confucian classics were forged to bolster his claims. Kang was a strong believer in constitutional monarchy and wanted to remodel the country after Meiji Japan; These ideas angered his colleagues in the scholarly class who regarded him as a heretic. Kang fled to Japan after failure of the reform, where with Liang he organized the Protect the Emperor Society, traveled throughout the Chinese diaspora promoting constitutional monarchy and competing with the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen's Revive China Society and Revolutionary Alliance for funds and followers.

After the Qing Dynasty fell and the Republic of China was established in 1912 under Sun Yat-sen, Kang remained an advocate of constitutional monarchy and with this aim launched a failed coup d'état in 1917. General Zhang Xun and his queue-wearing soldiers occupied Beijing, declaring a restoration of Emperor Puyi on July 1. This incident was a major miscalculation. The nation was highly . Kang became suspicious of Zhang's insincere constitutionalism and that he was merely using the restoration to become the power behind the throne. He abandoned his mission and fled to the American legation. On July 12, Duan Qirui easily occupied the city.

Kang's reputation serves as an important barometer for the political attitudes of his time. In the span of less than twenty years, he went from being regarded as an iconoclastic radical to an anachronistic pariah without significantly modifying his ideology.

The best-known and probably most controversial work of Kang Youwei was the Da Tongshu (大同書). The title of this book derives from the name of a utopian society imagined by Confucius, although it literally means "The Book of Great Unity." The ideas of this books appeared in his lecture notes from 1884, and encouraged by his students, he worked on this book for the next two decades, but it was not until his exile in India that he finished the first draft. The first two chapters of the book were published in Japan in the 1900s, however the book wasn't published in its entirety until 1935, about seven years after his death. In it Kang proposed a utopian future world that would be free of political boundaries, ruled by one central government, but under democratic rule. In his scheme, the world would be split into rectangular administrative districts which would be self-governing under a direct democracy, although oddly still loyal to a central world government.

His desire to end the traditional Chinese family structure defines him as an early advocate of women's independence in China. He reasoned that the institution of the family that had been practiced by society since the beginning of time was a great cause of strife. Kang hoped it would be effectively abolished. Replacing the family would be state-run institutions, such as womb-teaching institutions, nurseries and schools. Marriage would be replaced by one-year contracts between a woman and a man. Kang considered the contemporary form of marriage, in which a woman was trapped for a lifetime, to be too oppressive. Kang believed in equality between men and women and believed that there should be no social barrier barring women from doing whatever men can. From this point of view, Kang also advocated the idea that homosexuality should be permitted, as presumably there are no differences in love between a man and a woman and between two men or two women.

Kang saw capitalism as an inherently evil system and believed that government should establish socialist institutions to overlook the welfare of each individual. At one point he even advocated that government should adopt the methods of "communism", although it is debated what Kang meant by this term. He was surely one of the first advocates of Western communism in China. In this spirit, in addition to establishing government nurseries and schools to replace the institution of the family, he also envisioned government-run retirement homes for the elderly.

Notable in Kang's Da Tong Shu was his enthusiasm and belief in bettering humanity with technology. This was unusual for a Confucian scholar during his time. He believed that Western technological progress had a central role in saving humanity. While many scholars of his time continued to maintain the belief that Western technology should only be adopted to defend China against the West, he seemed to full-heartedly embrace the modern idea that technology is integral for advancing mankind. Before anything of modern scale had been built, he foresaw a global telegraphic and telephone network. He also believed that technology would reduce human labor to the point where each individual would only need to work 3 to 4 hours each day, a prediction that will be repeated by the most optimistic futurists later in the century.

When the book was first published it was received with mixed reactions. Due to Kang's support for the Guangxu Emperor, he is seen as a reactionary by many Chinese intellectuals. People of this camp believed that Kang's book was an elaborate joke, and that he was merely acting as an apologist for the emperor as to how utopian paradise could have developed if the Qing dynasty was not overthrown. Others believe that Kang was a bold and daring proto-Communist who advocated modern Western socialism and communism. Amongst those in the second school was Mao Zedong, who admired Kang Youwei and his socialist ideals in the Da Tongshu. Modern Chinese scholars nowadays often take the view that Kang was an important advocate of Chinese socialism, and despite the controversy Da Tongshu still remains popular.

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啟超, Liáng Qǐchāo; Courtesy: Zhuoru, 卓如; Pseudonym: Rengong, 任公) (February 23, 1873–January 19, 1929) was a Chinese scholar, journalist, philosopher and reformist during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), who inspired Chinese scholars with his writings and reform movements. He died of illness in Beijing at the age of 55.

In 1898, the Conservative Coup ended all reforms and exiled Liang to Japan, where he stayed for the next fourteen years of his life. While in Tokyo he was befriended by the influential Japanese politician (and future Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi. In Japan, he continued to actively advocate democratic notions and reforms by using his writings to raise support for the reformers’ cause among overseas Chinese and foreign governments. He continued to emphasize the importance of individualism, and to support the concept of a constitutional monarchy as opposed to the radical republicanism supported by the Tokyo-based Tongmeng Hui (the forerunner of the Kuomintang).

In 1899, Liang went to Canada, where he met Dr. Sun Yat-Sen among others, then to Honolulu in Hawaii. During the Boxer Rebellion, Liang was back in Canada, where he formed the "Save the Emperor Society" (保皇會). This organization later became the Constitutionalist Party which advocated constitutional monarchy. While Sun promoted revolution, Liang preached reform.

In 1900-1901, Liang visited Australia on a six-month tour which aimed at raising support for a campaign to reform the Chinese empire in order to modernize China through adopting the best of Western technology, industry and government systems. He also gave public lectures to both Chinese and Western audiences around the country. He returned to Japan later that year.

In 1903, Liang embarked on an eight-month lecture tour throughout the United States, which included a meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, DC before returning to Japan via Vancouver, Canada.

With the overthrow of the Qing dynasty, constitutional monarchy became an increasingly irrelevant topic in early republican China. He merged his renamed Democratic Party with the Republicans to form the new Progressive Party. He was very critical of Sun Yatsen's attempts to undermine President Yuan Shikai. Though usually supportive of the government, he opposed the expulsion of the Nationalists from parliament.

In 1915, he opposed Yuan's attempt to make himself emperor. He convinced his disciple Cai E, the military governor of Yunnan, to rebel. Progressive party branches agitated for the overthrow of Yuan and more provinces declared their independence. The revolutionary activity that he had frowned upon was utilized successfully. Besides Duan Qirui, Liang was the biggest advocate of entering World War I on the Allied side. He felt it would boost China's status and ameliorate foreign debts. He condemned his mentor, Kang Youwei, for assisting in the failed attempt to restore the Qing in July 1917. After failing to turn Duan and Feng Guozhang into responsible statesmen, he left politics.

Liang Qichao was both a traditional Confucian scholar and a reformist. Liang Qichao contributed to the reform in late Qing by writing various articles interpreting non-Chinese ideas of history and government, with the intent of stimulating Chinese citizens' minds to build a new China. In his writings, he argued that China should protect the ancient teachings of Confucianism, but also learn from the successes of Western political life and not just Western technology. Therefore, he was regarded as the pioneer of political friction.

Liang shaped the ideas of democracy in China, using his writings as a medium to combine Western scientific methods with traditional Chinese historical studies. Liang's works were strongly influenced by the Japanese political scholar Katō Hiroyuki (加藤弘之, 1836-1916), who used methods of social Darwinism to promote the statist ideology in Japanese society. Liang drew from much of his work and subsequently influenced Korean nationalists in the 1900s.

Liang Qichao’s historiographical thought represents the beginning of modern Chinese historiography and reveals some important directions of Chinese historiography in the twentieth century.

For Liang, the major flaw of "old historians" (舊史家) was their failure to foster the national awareness necessary for a strong and modern nation. Liang's call for new history not only pointed to a new orientation for historical writing in China, but also indicated the rise of modern historical consciousness among Chinese intellectuals.

During this period of Japan's challenge in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), Liang was involved in protests in Beijing pushing for an increased participation in the governance by the Chinese people. It was the first protest of its kind in modern Chinese history. This changing outlook on tradition was shown in the (史學革命) launched by Liang Qichao in the early twentieth century. Frustrated by his failure at political reform, Liang embarked upon cultural reform. In 1902, while in exile in Japan, Liang wrote New History (新史學), launching attacks on traditional historiography.

In the late 1920s, Liang retired from politics and taught at the Tung-nan University in Shanghai and the Tsinghua Research Institute in Beijing as a tutor. He founded Chiang-hsüeh she (Chinese Lecture Association) and brought many intellectual figures to China, including Driesch and Tagore. Academically he was a renowned scholar of his time, introducing Western learning and ideology, and making extensive studies of ancient Chinese culture.

During this last decade of his life, he wrote many books documenting Chinese cultural history, Chinese literary history and historiography. He also had a strong interest in Buddhism and wrote numerous historical and political articles on its influence in China. Liang influenced many of his students in producing their own literary works. They included Xu Zhimo, renowned modern poet, and Wang Li, an accomplished poet and founder of Chinese linguistics as a modern discipline

Yan Fu (simplified Chinese: 严复; pinyin: Yán Fù; Wade-Giles: Yen Fu; courtesy name: Ji Dao, 幾道; 8 January 1854 — 27 October 1921) was a Chinese scholar and translator, most famous for introducing western ideas, including Darwin's "natural selection," to China in the late 19th century.

Yan Fu studied at the Fujian Arsenal Academy (福州船政學堂) in Fuzhou, Fujian Province. In 1877–79 he studied at the Navy Academy in Greenwich, England. Upon his return to China, he was unable to pass the Imperial Civil Service Examination, while teaching at the Fujian Arsenal Academy and then Beiyang Naval Officers' School (北洋水師學堂) at Tianjin.

It was not until after the Chinese defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95, fought for control of Korea) that Yan Fu became famous. He is celebrated for his translations, including Thomas Huxley's , Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, John Stuart Mill's On Liberty and Herbert Spencer's Study of Sociology. Yan critiqued the ideas of Darwin and others, offering his own interpretations.

The ideas of "natural selection" and "survival of the fittest" were introduced to Chinese readers through Huxley's work. The former idea was famously rendered by Yan Fu into Chinese as tianze (天擇).

He became a respected scholar for his translations, and became politically active. In 1895 he was involved in the Gong Ju Shangshu movement. In 1912 he became the first principal of National Peking University (now Beijing University).

Emperor Guangxu was shocked at the seizing

of Jiaozhou Bay by force by Germany and said

he didn’t want to be a monarch of a dying country.

4. The Act of Petition indicated:

(1) Expression of patriotic passion and wish to participate in politics by way of petition by Kāng Yǒuwei and his fellow scholars.

(2) Demonstration of the strength of the intellectual group who broke the ban that literate could not interfere in politics.

(3) “Gong Ju Shang Shu—the Examinees’ Petition” lifted the curtain of the reform, which turned into political practice from publicity.

II、Actions—Set up Organizations and Publish Newspapers and Journals

1、Organization

|

Name |

Place |

Sponsor |

|

Strengthening Society |

Beijing |

Wēn Tíngshì文廷式 |

|

Strengthening Society |

Shanghai |

Kāng Yǒuwēi康有为 |

2、Newspaper and Journals:

|

Name |

Founder |

Place |

|

《News Home & Abroad》 |

Kāng Yǒuwēi |

Beijing |

|

Paper on Strengthening》 |

Kāng Yǒuwēi |

Shanghai |

|

《Current Affairs》 |

Liáng Qǐchaō |

Shanghai |

III:Climax—The Hundred Days’ Reform

1、Igniting Fuse:

(1)German Seizure of Jiaozhou Bay

(2)Kāng Yǒuwēi handed in 《The Memorial on an Overarching Scheme Requested by His Majesty应诏统筹全局折》.

2、The Indicator:On June 11, 1898, Emperor Guangxu issued the Edict –A Clear Statement on State Affairs.

3, The Process: From June 11 to Sept. 21, Emperor Guangxu issued a series of edicts relating to reforms in politics, economy, cultural and military aspects.

Main Contents of the Reform

Modernizing the traditional exam system

Elimination of sinecures (positions that provide little or no work but give a salary)

Creation of a modern education system (studying math and science instead of focusing mainly on Confucian texts, etc.)

Change the government from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy with democracy.

Apply principles of capitalism to strengthen the economy.

Completely change the military buildup to strengthen the military.

Rapidly industrialize all of China through manufacturing, commerce, and capitalism.

IV. Results--Frustration

1、Response from Society:

(1)National bourgeois and enlightened gentry: support

(2)Empress Dowager:To suppress at any time.

(3):Those seeking official positions by passing the national exam: Opposition

(4)Reformers: Seeking support from foreign powers and trying to win over Yuan Shikai.

2、Wuxu Coup—Failure of the Reform

(1)Time:Sept. 21,1898

(2)End:Empress Dowager Cixi engineered a coup d'état on September 21, 1898, forcing the young, reform-minded Guangxu into seclusion. The emperor was put under house arrest within the Forbidden City until his death in 1908. Cixi then took over the government as regent.

Táng Sìtóng, on the left, went to Yuán Shìkǎi for help, yet, Yuán informed Róng Lù the plan of the reformers.

谭嗣同 袁世凯

Evidence

Empress Dowager Cixi Edict pass Rong Lu in Beijing

A Photo of the Empress Dowager

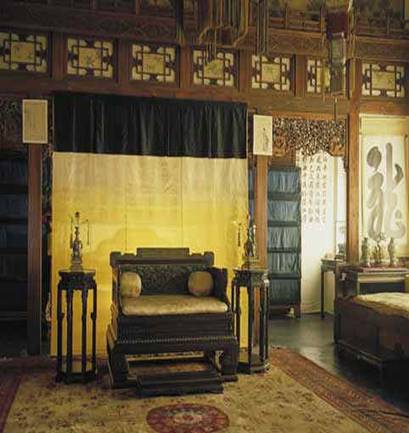

Yingtai in Zhongnanhai is where Emperor Guangxu was under house arrest

The Hall of Happiness and Longevity in the Summer Palace was where Cixi and Rong Lu decided to stage a coup

2、Wuxu Coup—Failure of the Reform

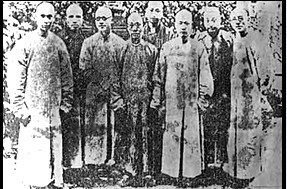

The Hundred Days' Reform ended with the rescinding of the new edicts and the execution of six of the reform's chief advocates, together known as the "Six Gentlemen" (戊戌六君子): Tan Sitong, Kang Guangren (Kang Youwei's brother), Lin Xu (林旭), Yang Shenxiu, Yang Rui (reformer) and Liu Guangdi. The two principal leaders, Kang Youwei and his student Liang Qichao, fled to Japan to found the Baohuang Hui (Protect the Emperor Society) and to work, unsuccessfully, for a constitutional monarchy in China. Another leader of the reform, Tan Sitong, refused to flee and was arrested and executed.

3. What caused the failure?

A、Fundamental reason: The bourgeois was took weak.

B、Main Cause: the conservatives were too strong.

C、Reformers made mistakes in their strategy.

Ensuing Happenings

In the decade that followed, the court belatedly put into effect some reform measures. These included the abolition of the Imperial Examination in 1905, educational and military modernization patterned after the model of Japan, and an experiment in constitutional and parliamentary government. The suddenness and ambitiousness of the reform effort actually hindered its success. One effect, to be felt for decades to come, was the establishment of the New Army, which, in turn, gave rise to warlordism.

On the other hand, the failure of the reform movement gave great impetus to revolutionary forces within China. Changes within the establishment were seen to be largely hopeless, and the overthrow of the whole Qing government increasingly appeared to be the only viable way to save China. Such sentiments directly contributed to the success of the Chinese Revolution in 1911, barely a decade later.

C、The Legacy of the Hundred Days’ Reform

1、Nature: It was a political patriotic movement aimed at saving the country, as well as a mind emancipation.

2、Significance:

(1)The wave of new ideas heralded a new era.

(2)The reform injected fresh air into the stale society of China.

(3)The printing industry gained speed.

(4)Outmoded conventions and backward habits were being replaced by new ways of living

(5)Modern cultural and education

(6)Left a spiritual legacy to later generations.

Differing Interpretations

The traditional view portrayed the reformers as heroes and the conservative elites, particularly the Empress Dowager Cixi, as villains unwilling to reform because of their selfish interests. However, some historians in the late 20th century have taken views that are more favorable to the conservatives and less favorable to the reformers. In this view, Kang Youwei and his allies were hopeless dreamers unaware of the political realities in which they operated. This view argues that the conservative elites were not opposed to change and that practically all of the reforms that were proposed were eventually implemented.

For example, Sterling Seagrave, in his book "The Dragon Lady", argues that there were several reasons why the reforms failed. Chinese political power at the time was firmly in the hands of the ruling Manchu nobility. The highly xenophobic Ironhats faction dominated the Grand Council and were seeking ways to expel all Western influence from China. When implementing reform, the Guangxu Emperor by-passed the Grand Council and appointed four reformers to advise him. These reformers were chosen after a series of interviews, including the interview of Kang Youwei, who was rejected by the Emperor and had far less influence than Kang's later boasting would indicate. At the suggestion of the reform advisors, the Guangxu Emperor also held secret talks with former Japanese Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi with the aim of using his experience in the Meiji Restoration to lead China through similar reforms.

It has also been suggested, controversially, that Kang Youwei actually did a great deal of harm to the cause by his perceived arrogance in the eyes of the conservatives. Rumours about potential repercussions, many of them false, made their way to the Grand Council, and were one of the factors in their decision to stage a coup against the Emperor. Kang, like many of the reformers, grossly under-estimated the reactionary nature of the vested interests involved.